Ill-fated Arctic expedition continues to captivate us some 170 years later

Crozier’s note was discovered eleven years later, and for the next 160 years explorers, scientists and enthusiasts followed the clues he left in an attempt to solve the mystery of what lay behind the biggest disaster in the history of polar exploration.

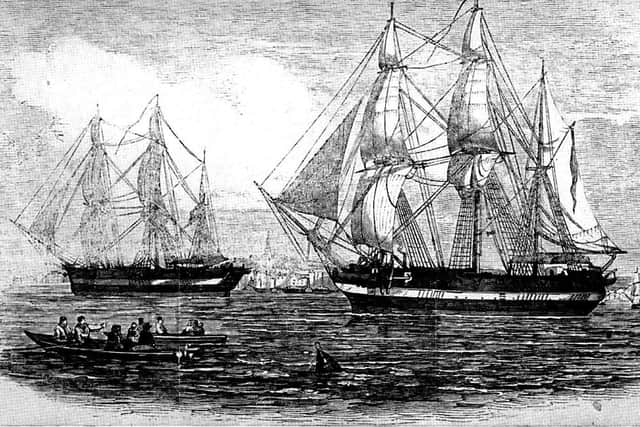

The most significant breakthrough has come in recent years with the remarkable discovery of the expedition ships, Erebus and Terror, lying in shallow waters above the Arctic Circle. Crozier did not launch the crusade for clues, but his message sent the crusaders in the right direction.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe precise wording of Crozier’s message was: “And start on tomorrow 26th for Backs Fish River.”

Although ambiguous and lacking much detail, the note at least revealed Crozier’s intentions and gave generations a clear indication of where to search in the vast, scarcely populated Arctic wastelands stretching for at least 800,000 square miles (over 2,000,000 square kilometres).

The crucial document, which was found in 1859, was a regulation navy form traditionally left to indicate a vessel’s geographic position to those sent in search of a missing ship. Most of the words added to the printed document were written in the margins by the captain of Erebus, James Fitzjames, who outlined past events, such as the party’s geographical position at the time of abandoning the ships and news of the expedition leader, Sir John Franklin’s, death.

Crozier’s short message, which is squeezed into a corner of the document and appears almost as an afterthought, is the only surviving written clue to the expedition’s plans for escape. Due to the lack of space, he wrote the short message upside down in the corner of the document.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a pivotal discovery which sent generations to the barren area along the western and southern coasts of King William Island, leading to a trail of skeletons, scattered debris and ultimately the wrecks of Erebus and Terror. One authority said it was “the most evocative document in the long history of Western exploration of the Arctic regions”.

The unfortunate venture is generally known as the Franklin Expedition after Sir John Franklin, who was appointed as leader at the outset. However, Franklin had died a year before Crozier wrote his terse message. While Franklin led his men into the jaws of the ice, the responsibility for leading them out fell into the hands of Captain Crozier.

The search which followed was extraordinary by any standards. The North West Passage expedition initially left London in May 1845 and was last seen on the edge of Baffin Bay in July of the same year, with all 129 on board Erebus and Terror reportedly in good spirits. The first relief expeditions were sent north in 1848 and over the next few years around forty ships combed the labyrinth of Arctic waterways in a vain attempt to trace the missing men. The official naval search ended in 1854, nine years after the expedition sailed, and the privately financed Fox expedition under the leadership of Leopold McClintock discovered the document and Crozier’s key message in 1859.

McClintock’s return was the signal for the start of an unprecedented quest to uncover what happened to Crozier and his party. Over the next 160 years, at least fifty official and unofficial expeditions ventured into the Arctic, hoping to solve the mystery or to retrieve scattered relics from the snow. The true number of searches is impossible to calculate because so many private groups travelled unannounced to the area. However, more parties went in search of the dead than were ever sent to find the living.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA breakthrough was achieved in 2014 and 2016 when specialist teams found the expedition’s ships, Erebus and Terror, on the sea floor in remote waters above the Arctic Circle. Experts believe the hugely significant discoveries will go a long way towards answering many questions and are eagerly analysing the large variety of objects already retrieved from the depths.

However, locating the ships is only the first stage of a long and complex process. Assorted relics like the ship’s bell from Erebus, Victorian era scientific instruments and discarded clothing and shoes were the first objects recovered. But the biggest prizes yet to be claimed are the expedition’s logbooks, charts and even personal letters which experts believe have survived decades under water and can be safely reclaimed for historians to pore over and analyse. Overall, the full investigation of the secrets kept by Erebus and Terror will take at least ten years or possibly more.

It will also provide an important opportunity to explore the remarkable story of Captain Crozier, particularly as there was considerably more to Crozier’s life than an unrecorded death somewhere in the Arctic.

Crozier was among the most prolific and under-valued explorers of the age. He entered the navy as a child, survived the brutal Napoleonic War and emerged to sail with great distinction on six expeditions to the ice in an outstanding naval career lasting almost forty years. Crozier was deeply involved in the nineteenth century’s three great endeavours of maritime discovery – navigating the North West Passage, reaching the North Pole and mapping Antarctica. Only Crozier’s great friend, Sir James Clark Ross braved more polar expeditions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is a perception that all the great stories from the history of polar exploration involve the outstanding figures of the ‘heroic age’ of Antarctic discovery in the early twentieth century, such as Roald Amundsen, Tom Crean, Robert Scott and Ernest Shackleton. All are rightly saluted for their memorable exploits, yet to focus entirely on this era would be mistaken. There are other half-forgotten explorers who made history and yet have been neglected by history. Such a man was Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier.

I have always nursed a fondness for the unsung hero, the neglected individual whose character and achievements are underestimated or have been overlooked by history. It was this curious fascination that led me to write the first biography of the indestructible Irish polar explorer, Tom Crean. The title, An Unsung Hero, seemed singularly appropriate.

Crozier is another unsung hero. He was an exceptional explorer poorly treated by history, who deserves far wider recognition for accomplishments that would have been remarkable in any age of exploration. Helped by the new discovery of Erebus and Terror, we now have the perfect moment to re-open the file on Crozier.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.