Derry Halloween: Abhartach, the Vampire

People over the years have thought that Dracula was based on that old Romanian prince, Vlad the Impaler, who had a nasty habit of killing those who opposed him in a rather bloodthirsty manner. However, the truth may be closer to home.

In the north Derry area, between the towns of Garvagh and Dungiven, in a district known as Glenullin, the glen of the eagle, we may find a clue to Dracula’s origins. In the middle of a field in the remote townland of Slaughtaverty is an area known locally as the ‘Giant’s Grave’ but it might be more accurately described as Abhartach’s tomb.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the grave there is a curling thorn bush, under which lies a large and heavy stone. Originally there were more stones, the remnants of an old monument, but these have been removed over time by local farmers for building purposes. However, there is little doubt that the tomb was once an imposing structure and that it gave the townland its name.

But who was Abhartach?

During the fifth and sixth centuries, the Glenullin area was a patchwork of petty kingdoms, each with its own local ruler or ‘king’. These kings may have been little more than tribal warlords. There is ample evidence of their rule as the countryside is dotted with hill forts, ancient raths and early fortifications marking their respective territories. Abhartach, according to tradition, was one of these chieftains.

Local descriptions of him vary. Some say he was deformed in some way and others say that he was a dwarf. However, most accounts agree that he was a powerful wizard and was extremely evil. Abhartach was a jealous and suspicious man who trusted no one, not even his wife, who he was convinced was having an adulterous affair. He decided to catch her in the act. One night he climbed out one of the windows of their castle and crept along a ledge towards his wife’s bedroom. However, either because of his deformity or poor balance, he slipped and fell to his death. His body was found the following morning and the people of the town quickly buried him. He was a high-ranking chieftain with the same rights as a king, so he was buried standing upright, which was the custom at the time. The following day, Abhartach returned and demanded that each of his subjects cut their wrist and gather the blood in a bowl. They were told to do this and deliver the blood to him each day in order to sustain his life. Too terrified to refuse, they did as he ordered.

Eventually, the people decided that they could not live in fear of Abhartach any longer. They hated him when he was alive, but now that he had returned as one of the marbh bheo, or the living dead, they were terrified of what he could do to them. They decided to hire an assassin to kill him. They persuaded another chieftain, Cathán, to perform the deed for them. Cathán slew Abhartach and buried him once again, standing up in an isolated grave. However, the following day Abhartach returned, as evil as ever, and once again demanded a bowl of blood, drawn from the veins of his subjects, in order to sustain his vile corpse. In great terror, the people asked Cathán to slay him once more. This Cathán did, burying the corpse as before. However, the following day, Abhartach returned again, demanding the same gory tribute from his people.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDepending on which version of the folk tale you hear, Cathán was puzzled and consulted either a local druid or an early Christian saint about why Abhartach could not be killed. There are several ‘hermitages’ in the area. According to tradition, these were the dwellings of particularly holy men. The most notable is in Gortnamoyagh Forest on the very edge of Glenullin, where local people will still point out ‘the saint’s track’, a series of stations near a holy well. Close by was said to have been the hermitage of a saint known as Eoghan, or John, who is credited with having founded a place of Christian worship in the area (the site is still known as Churchtown, although any related foundation has long since vanished).

A ‘footprint’ on a stony prominence in the forest is also attributed to this saint. It is said that from here he flew from Gortnamoyagh to say Mass in his own foundation. His name appears in several local place names, such as Killowen in Coleraine (about fifteen miles away) and Magilligan (about twenty miles away). It was to this Druid or saint that Cathán is believed to have gone. The venerable old man listened long and hard to the chieftain’s tale. When Cathán had finished, the old man said to him, ‘Abhartach is not really alive. Through his devilish arts he has become one of the undead. He has become a drinker of human blood. He can’t actually be slain but he can be restrained.’

He then proceeded to give the astonished Cathán instructions as to how to ‘suspend’ the vampiric creature.

‘Abhartach must be slain with a sword made from yew wood and must be buried upside down in the earth,’ said the old man. ‘Thorns and ash twigs must be sprinkled around him and a heavy stone must be placed directly on top of him. Should the stone be lifted, however, he will be free to walk the earth once more.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCathán returned to Glenullin and did what the holy man had told him. Abhartach was slain with a wooden sword and buried upside down. Thorns were placed all around the gravesite. On top of the grave, Cathán built a great tomb which could be seen for miles around. This has now vanished but the stone remains and a tree, which grew from the scattered thorns, rises above it.

The land on which the grave is situated has acquired a rather sinister reputation over the years. Locally it is considered to be ‘bad ground’ and has been the subject of a number of family disagreements. In 1997, attempts were made to clear the land, but, if local tradition is to be believed, workmen who tried to fell the tree found that their brand-new chainsaw stopped for no reason on three occasions.

When attempting to lift the great stone, a steel chain suddenly snapped, cutting the hand of one of the labourers and, significantly, allowing blood to soak into the ground. Although legends still abound in the locality of the ‘man who was buried three times’ and the fantastic treasure that was buried with him, few local people will approach the grave, especially after dark.

This, then, in essence is the legend with its folkloric additions. But is it simply an isolated tale or does it fit into a tradition of Irish tales of vampires? The spilling of blood was not uncommon amongst the ancient Irish – indeed animal blood was ritually let under Christian directive upon St Martin’s Eve (11 November). The roots of this tradition undoubtedly go back to pagan times and may have a connection with the returning dead.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe horrors of the famine added considerably to the lore. The blood of pigs and cows supplemented a meagre diet, either drunk raw or made into relish cakes (a mixture of meal, vegetable tops and blood brought together in a kind of patty).

Although most cultures have vampire stories, such tales have a particular resonance in Ireland. Here, interest in and veneration of the dead seems to have played a central part in Celtic thinking. However, it was the historian and folklorist Patrick Weston Joyce who actually made connections between Abhartach and the Irish vampire tradition. Joyce enthusiastically recounted the legend in his own book A History of Ireland (1880). This was seventeen years before Dracula was published and it is believed that Stoker, then a Dublin civil servant, read Joyce’s work (and presumably the Abhartach legend) with some relish. Around the same time, manuscript copies of Geoffrey Keating’s History of Ireland, which made much of the undead, were placed on public display in the National Museum in Dublin. They were on loan from Trinity College Library (which possessed two manuscript copies) and the display included chapter ten on the undead. Although Stoker himself could not read Irish, he had many friends and acquaintances that did and he may have received at least part of the work in translation.

So there you have it. Could the legend of the vampire king, coupled with the strong tradition of blood-drinking Irish chieftains and nobles, be responsible for giving birth to the gothic tale of Count Dracula? Can we really consign the vampire to some remote part of Eastern Europe, where he is unlikely to do us any harm, or should we keep a clove of garlic handy?

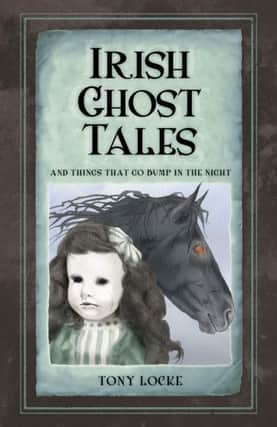

From Irish Ghost Tales

Tony Locke (The History Press Ireland, 2015)