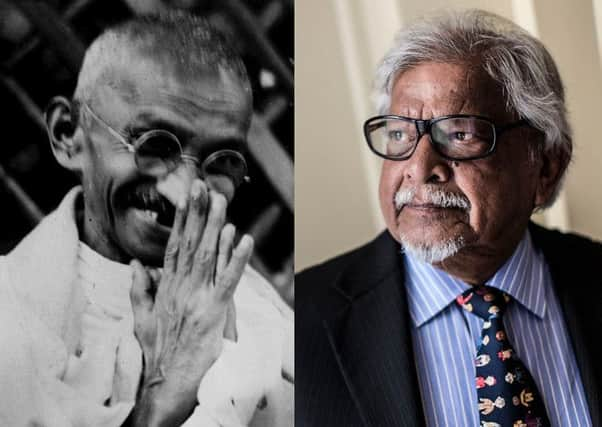

My grandfather Gandhi believed in zero waste and social justice

Last Thursday, Dr Gandhi visited Magee to deliver the inaugural John Hume and Thomas P O’Neill Chair in Peace lecture under the Chairmanship of Professor Brandon Hamber and impart some of that wisdom to those working to further embed peace in Londonderry and elsewhere.

For three decades Dr Gandhi worked for the largest-selling English language newspaper in the world, The Times of India, but unjaded by his years as a hack, he now travels the world preaching his granda’s inspirational message of peace and non-violence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Gandhi told the audience in the Great Hall how his parents packed him off to his grandfather from Smuts’ proto-Apartheid South Africa in the mid 1940s because he had been getting racist stick from the whites for being “too black” and from the blacks for being “too white” in the racially segregated society.

It was sitting at his grandfathers knee Dr Gandhi learned the lessons of peace and understanding that he seeks to keep alive despite the fires of violence and warfare glowing throughout the world.

It’s a tough sell in a 21st century where the ‘wretched of the earth’ are as likely to find solace in Mao Tse-tung’s dictum that “power grows out of the barrel of a gun” as they are in Mohandas Gandhi’s turn-the-other-cheek philosophy, when they are faced with one jackboot or another on their necks. Neither are those wearing the jackboots, needless to say, shy of employing violent methods to maintain or further their interests.

But Dr Gandhi and the new Peace Chair are undeterred, although Professor Hamber acknowledged that whilst lots has been done there’s more, lots more, to do.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIntroducing Dr Gandhi Professor Hamber listed the positives: the decline in inter-state war since the last two world wars; peace by degrees in South Africa, Northern Ireland, Sierra Leone and Liberia; dictatorships toppled in Latin America; greater vigilance against genocide thanks to modern technology. Notwithstanding this peace-building is still an uphill battle.

“What we also know is that 50 per cent of societies that are set to be post-conflict actually slide back into conflict within five years,” admitted Professor Hamber.

“Since 2001, there’s actually been on average ten civil wars every single year. One in four people on the planet, that’s more than 1.5billion, in fact, live in fragile or conflict affected societies. Probably many of you might not know but 5.4m people have died in the Democratic Republic of Congo since 1998. 65.3million people, that’s one in 113, were displaced from their homes by conflict and persecution in 2015 alone,” said the new Peace Chair.

“When I was in Colombia recently, that’s where I met Dr Gandhi, I learned 6million victims had been displaced from their homes and lost land and loved ones. Since 2003 what we now sort of think of as the forgotten war that took place in Iraq, 250,000 people have been killed in that conflict. And in five years of the Syrian war 471,000 people have been killed, that’s 11 per cent of the entire population of Syria,” he added.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Gandhi explained how his grandfather taught him that the solution to ending the cycle of violence was both internal and societal and that ‘Mahatma’ did not merely believe in ‘peace’ as an entrenchment of the status quo but he also believed in fairness, equality and respect as a means of building social justice and uprooting violence at its source.

He said his grandfather taught him that there are other forms of violence other than the obvious physical manifestations that can result in mayhem, murder and chaos.

“Like discrimination, oppression, hate, prejudice, wasting resources, overconsumption of things, hundreds of things that we do every day unconsciously,” he said.

“He [Mahatma] said: ‘We commit passive violence every day, consciously and unconsciously and that generates anger in the victim and the victim then resorts to physical violence to get justice.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“‘It is passive violence that fuels the fire of physical violence, so logically if we want to end the fire of physical violence we have to cut off the fuel supply and since the fuel supply comes from each one of us, we have to become the change that we wish to see in the world.’

“‘If we don’t change ourselves and change our attitudes we are never going to be able to create the peace, the lasting peace that we all want.’

“In his concept, peace was when all of us would live in harmony, with nature and with each other, because only then would we have true peace.”

Dr Gandhi echoed the latter day clarion call of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement in stating that there can be no peace without justice, whilst firmly eschewing violence and revenge as a legitimate or useful response.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Just simply ending war was not enough, we have to learn to create that harmony.

“Today our education system unfortunately is simply about giving them [pupils] careers where they can go off and make a lot of money. It’s all about materialism, it’s all encouraging materialistic lifestyle and materialism and morality has an inverse relationship.

“The more materialistic we become the less moral we are and we can see this in every day life all the time.

“So we have to be conscious of this and we have to make all these different efforts to bring about that kind of peace.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Gandhi said he learned this anti-materialist and ‘Zero Waste’ message from ‘Mahatma’ shortly after arriving in India from South Africa as a youngster.

“It is also very important for us to remember that his philosophy of non-violence is not simply a philosophy for ending war or ending violence. It has much deeper connotations and I realised this one day through a little pencil.

“A little three inch butt of a pencil became the subject for a major lesson. I was coming back from school and I had this little three inch pencil in my hand and I thought I deserved a better pencil.

“This was too small for me and without a second thought I just threw the pencil away on the roadside because I was so sure that grandfather would give me a new pencil when I asked him for one.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But that evening when I asked grandfather for a new pencil, instead of giving me one, he subjected me to a lot of questions. He wanted me to know how the pencil became small, and where did I throw it away and why did I throw it away and on and on.

“And I couldn’t understand why he was making such a fuss over a little pencil and so he told me to go out and look for it.

“And I said: ‘You must be joking! You don’t expect me to out and look for a little pencil in the dark?’

“He said: ‘Oh yes, I do. Here’s a flashlight.’

“And he sent me out with a flashlight to look for this pencil and I think I must have spent two hours searching for it and when I finally found it and brought it to him he said: ‘Now I want you to sit here and learn two very important lessons.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“‘The first lesson is that even in the making of a simple thing like a pencil we use a lot of the world’s natural resources and when we throw them away we are throwing away the world’s natural resources and that is why it is against nature.’

“‘The second lesson is that, because in an affluent society we can afford to buy all these things in bulk we overconsume the resources of the world and because we over consume them we are depriving people elsewhere of these resources and they have to live in poverty and that is why it is against humanity.’

“And that was the first time I realised that all of these little things that we do every day, consciously and unconsciously, things that have become so much a part of our nature, because of the culture of violence that we live in, that all these things are acts of violence.”

Dr Arun said he was grateful at having had the opportunity of learning these lessons from his grandfather as a 12-year-old boy even during the epoch-making final years of his life when ‘Mahatma’ was busy negotiating Indian independnence with the United Kingdom and other national leaders from the subcontinent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I had the privilege as a young boy to go and stay with him between the age of 12 and 14 and although the lessons he taught me were very simple and modest lessons and understandable for a 12 or 13 year old boy, there was a profound meaning to those lessons.

“And when I grew up and began to reflect on these lessons I realised how important they were to his philosophy as well as to our personal lives because one of the things he emphasised during his life was that peace has to begin with us, each one of us.

“We cannot live peace outside if we are not at peace with ourselves and how do we become peaceful within ourselves.”