Watch: NI is sick and violence may very well re-emerge: Haass’ bald assessment

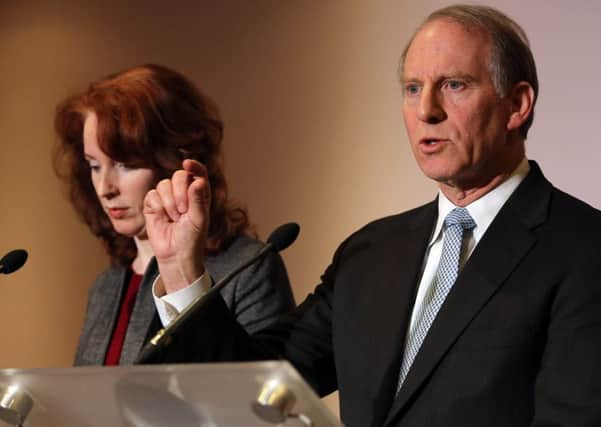

Mr Haass briefed the committee on his recent sojourn in Northern Ireland where despite his best efforts at mediation, an agreed way of dealing with the past proved elusive.

“It’s traumatised psychologically, physically, economically and politically,” said Mr Haass. “There are all sorts of divisions, wounds, damage and the like, and obviously North Korea [sic]...Northern Ireland - I apologise - was no exception and one day North Korea will be no exception.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I look forward to that day happening, when it gets out from under the rule and division it has known.

“And what this showed to me was that even though Northern Ireland had emerged from the Troubles and most of the violence had stopped, it had not become anything remotely like a normal society,” he told the committee.

Mr Haass spoke about the difficulty in establishing agreed mechanisms that dealt with the past whilst enjoying broad legitimacy and support.

Whilst he didn’t spell it out the Historical Enquiries Team (HET) - a division within the PSNI - has not enjoyed this broad support, especially not within loyalism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat’s why Haass proposed a new Office for Parades, Select Commemorations, and Related Protests (OPSCRP) and a new Authority for Public Events Adjudication (APEA) to deal with parades; a new Commission on Identity, Culture, and Tradition (CICT) to deal with flags; and a new Historical Investigations Unit (HIT), a new Independent Commission for Information Retrieval (ICIR), and a new Implementation and Reconciliation Group (IRG) to deal with the past.

The diplomat warned that if the past was not dealt with violence could well return to the streets of Northern Ireland.

He referred to the interface barriers that divide the community in Belfast and the fact that upwards of 90 per cent of young people are educated on a sectarian basis.

“I don’t see the society sowing the seeds of its own normalisation, of its own unity, if neighbourhoods and schools are still divided.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“What worries me in that kind of an environment, particularly where politics are not shown to be making progress, alienation will continue to fester, and violence, I fear, could very well re-emerge as a characteristic of daily life.

“So, it’s premature to put Northern Ireland, as much as we’d like to, into the outbox of problems solved.

“I’d love for it to be there and I look forward to that day but quite honestly it is not there yet,” he said.

Mr Haass made the comments a year after the Sentinel reported that analysts at US intelligence firm Stratfor were warning the economic failure of Northern Ireland had the potential to become a recruiting sergeant for violent groups.His blunt assessment comes a week after former US President Bill Clinton told Londonderry local politicians needed to ‘finish the job’ of building peace.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Chairman of the committee said he hoped visiting dignitaries from the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland would be appraised of Mr Haass’ analysis when they are going through the St Patrick’s Day motions this week.

Mr Haass said: “I do believe this is a society that will not be able to get beyond what it’s gone through unless there is something of a political but also psychological process of contending with it, otherwise, what will happen is different communities will live with their own different versions of the past and I came away thinking that there would never be the kind of bridge-building and normalisation, we and they want to see, without a multidimensional approach to dealing with what happened.”